by Gert Fischer | Oct, 2025 | Bonn Sights, famous people from Bonn, history, points of interest

In 2025, the Fördergesellschaft für den Alten Friedhof Bonn e.V. (Friends of Bonn’s Old Cemetery Association) celebrates its 50th anniversary. The Bonn Greeters would like to offer their heartfelt congratulations! Through its work, the association makes an important contribution to the preservation and maintenance of one of Bonn’s most significant historical landmarks.

The so-called ‘Old Cemetery’ is easy to overlook. It is surrounded by walls and squeezed between three main roads and the railway line. Its entrance is at the beginning of Bornheimer Straße, almost directly next to the town hall. When you walk through the gate you enter another world. Graves from times long past lie in the shade of tall trees. Weathered gravestones and rusted wrought-iron crosses dominate the scene. Some are crooked. Many of the graves are obviously no longer maintained and are overgrown. The traffic noise fades into the background and birdsong dominates. It is no wonder that feature films are occasionally shot here. Fog machines are turned on and eerie figures stride through the night. The rattling of the railway is suppressed.

The so-called ‘Old Cemetery’ is easy to overlook. It is surrounded by walls and squeezed between three main roads and the railway line. Its entrance is at the beginning of Bornheimer Straße, almost directly next to the town hall. When you walk through the gate you enter another world. Graves from times long past lie in the shade of tall trees. Weathered gravestones and rusted wrought-iron crosses dominate the scene. Some are crooked. Many of the graves are obviously no longer maintained and are overgrown. The traffic noise fades into the background and birdsong dominates. It is no wonder that feature films are occasionally shot here. Fog machines are turned on and eerie figures stride through the night. The rattling of the railway is suppressed.

The cemetery has been in existence since 1715. At that time, it was located just outside the city fortifications. It owes its triangular layout to the fork in the road where Archbishop Elector Joseph Clemens – better known as the creator of the residential palace, now the university – had it laid out. It was originally intended for soldiers, strangers and poor people, i.e. those whose families did not have graves in the inner-city cemeteries. In 1787, it became the city’s only cemetery: Elector Max Franz closed the parish cemeteries and turned it into a ‘general burial ground’. The reason for this was the realisation that the overcrowded churchyards posed a health risk to the city’s population. In this respect, Bonn was ahead of its time. In most other cities in the Rhineland, such measures were only ordered during French rule after 1794.

The Old Cemetery retained its function as ‘the’ Bonn cemetery until its closure in 1884. From then on, burials were only permitted if the family already had a grave on the site, as there was no more room for expansion. The cemetery was surrounded by buildings on all sides.

An information board at the entrance, as well as the Fördergesellschaft’s website, offer maps and a detailed overview of the VIP tombstones . There is much more to discover than the graves of Beethoven’s mother, Clara and Robert Schumann, Barthold Georg Niebuhr or Ernst Moritz Arndt, because the Old Cemetery reflects the history of bourgeois Bonn in the 19th century. In addition to the graves of well-known and lesser-known Bonn families, the resting places of university professors also play an important role. This part of the cemetery register reads like a “Who’s Who” of the German scholarly world of that time. Scattered across the grounds, we also find traces of the British colony, which was important for the social history of the city. Somewhat hidden away are the graves of French soldiers from the war of 1870/71. Added to this is the art-historical dimension. A tour of the cemetery is always a journey through the representative funeral culture of the 19th century. Particularly important are the cemetery chapel – built in the 13th century as the chapel of the Teutonic Order in Ramersdorf and moved here in the 1840s as an early example of monument preservation – and the former market cross of the medieval market in Dietkirchen in the north of Bonn.

Another treasure of the Old Cemetery is its trees, some of which date back to the 19th century. This is where problems become apparent: in some places, monument preservation and nature conservation compete with each other, as the tree roots threaten historic graves. Nowhere is this more evident than at the grave of Ernst Moritz Arndt, where the oak tree he planted himself almost 200 years ago is in the process of overturning the gravestones.

Another treasure of the Old Cemetery is its trees, some of which date back to the 19th century. This is where problems become apparent: in some places, monument preservation and nature conservation compete with each other, as the tree roots threaten historic graves. Nowhere is this more evident than at the grave of Ernst Moritz Arndt, where the oak tree he planted himself almost 200 years ago is in the process of overturning the gravestones.

Another problem is that the majority of the graves are no longer in use. The families have died out or now bury their members elsewhere. This means that time has practically stood still. This is a major challenge for the city, because although it can preserve the site as a whole, it does not have the resources to maintain the countless unused graves, let alone preserve the gravestones, apart from the graves of honour. On the other hand, ‘clearing’ the graves after the burial periods have expired, as is customary in normal cemeteries, is not an option due to the historical significance of the site and the existing monument protection. The support association helps to solve this dilemma. Among other things, it is responsible for the restoration of graves of historical or art-historical significance.

Another option is the ‘grave sponsorships’ arranged by the support association. In this case, the sponsors take over the maintenance of an abandoned grave, including the restoration of the gravestone, and thus acquire the right from the city of Bonn to be buried in this grave sometime in the future. Not everyone may like the idea of lying under someone else’s gravestone and being limited to a modest stone cushion with their own name on it. And some people also consider it morbid for someone to maintain their own grave during their lifetime. However, my wife and I find it somehow reassuring to know where we will end up – if nothing else comes in between.

by Gert Fischer | Aug, 2025 | EN, famous people from Bonn, history, Music, tradition

Nowadays, Beethoven festivals are almost routine. They take place annually. There is stable funding (we will draw a veil over the years 1993 to 1998), early planning by the artistic director and a firm foothold in the city’s society. At the first Beethoven Festival in 1845, everything was very different.

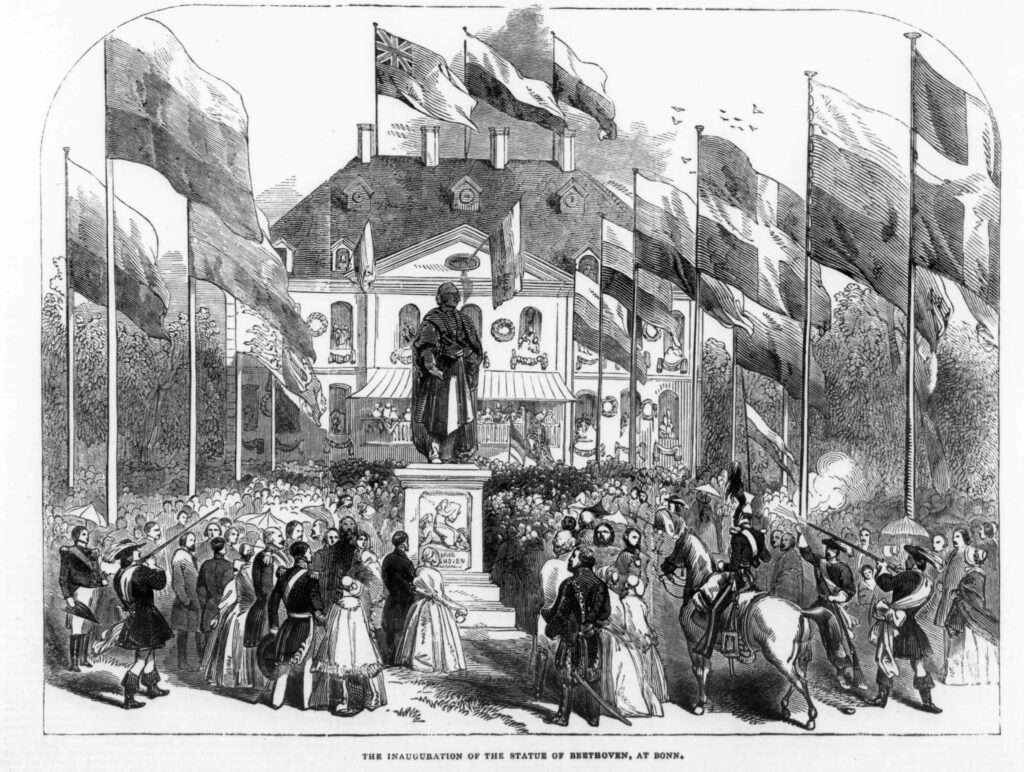

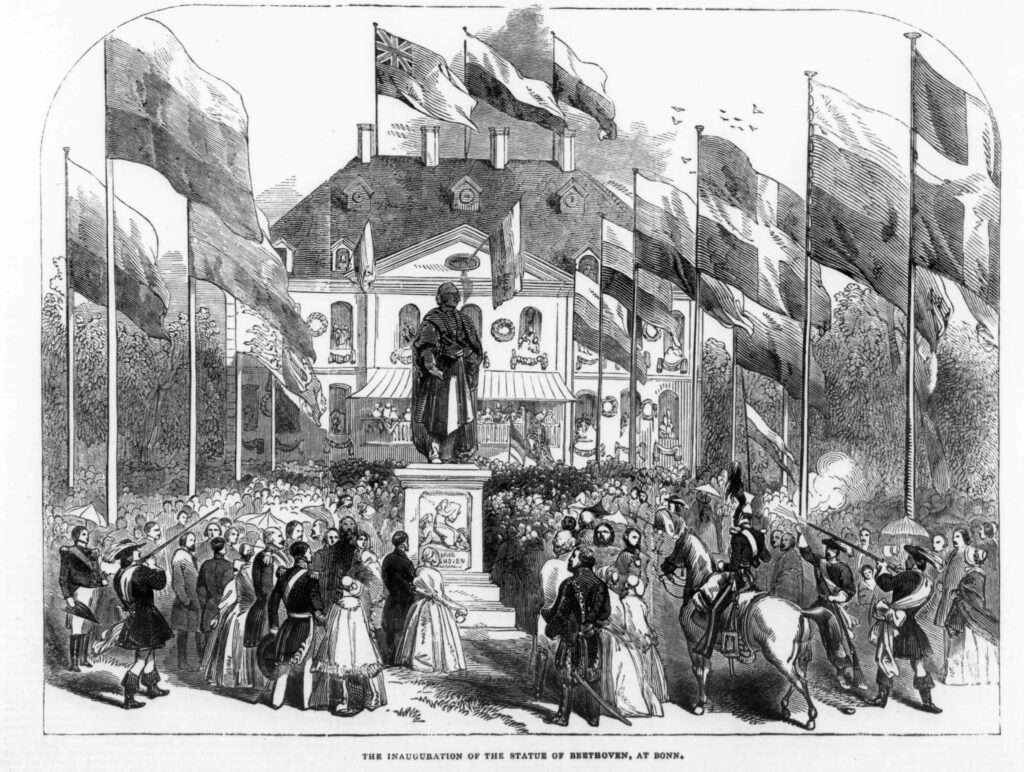

The occasion for the celebrations was not only the 75th birthday of the master, who died in 1827, but above all the inauguration of the Beethoven monument by the Dresden sculptor Ernst Hähnel on Münsterplatz. It all stemmed from what we would today call a ‘civic initiative’. At its helm was August Wilhelm Schlegel, one of the greats of the German scholarly world. His successor was a less fortunate choice. Heinrich Carl Breidenstein, the university’s ‘music director’, was a proven expert but had a difficult character. He was always controversial in Bonn society and was also openly attacked due to his enthusiasm for modern music (apart from Beethoven, he admired Liszt and Berlioz). He was simply not up to the task of organising a music festival with hundreds of guests in a small town without infrastructure or experience (Bonn had less than 20,000 inhabitants at the time). The matter was further complicated by the fact that King Frederick William IV and his guest Queen Victoria intended to attend. The support of Franz Liszt, which had already been needed to finance the monument, was a double-edged sword. Liszt’s connections were helpful, but his exuberant self-confidence was not. He polarised opinions and virtually invited criticism.

The occasion for the celebrations was not only the 75th birthday of the master, who died in 1827, but above all the inauguration of the Beethoven monument by the Dresden sculptor Ernst Hähnel on Münsterplatz. It all stemmed from what we would today call a ‘civic initiative’. At its helm was August Wilhelm Schlegel, one of the greats of the German scholarly world. His successor was a less fortunate choice. Heinrich Carl Breidenstein, the university’s ‘music director’, was a proven expert but had a difficult character. He was always controversial in Bonn society and was also openly attacked due to his enthusiasm for modern music (apart from Beethoven, he admired Liszt and Berlioz). He was simply not up to the task of organising a music festival with hundreds of guests in a small town without infrastructure or experience (Bonn had less than 20,000 inhabitants at the time). The matter was further complicated by the fact that King Frederick William IV and his guest Queen Victoria intended to attend. The support of Franz Liszt, which had already been needed to finance the monument, was a double-edged sword. Liszt’s connections were helpful, but his exuberant self-confidence was not. He polarised opinions and virtually invited criticism.

When Liszt arrived in Bonn a few weeks before the festival, at which he was to conduct alongside court conductor of Kurhessen Spohr, he immediately made his mark. He flatly rejected Breidenstein’s idea of using the Hussars’ riding arena in front of the northern city wall as a concert hall – according to a contemporary source, a ‘stinking hut’. The result was perhaps the greatest miracle in Bonn’s architectural history, which is otherwise not particularly rich in miracles: in less than two weeks, a consortium of Bonn carpenters, with the support of Cologne cathedral master builder Zwirner, erected a wooden festival hall in the ‘Raess’schen Gärten’. Today, we know this area as the car park in the Viktoriakarrée. With a height of around 7 metres, the building measured approximately 62 × 23 metres. However, it is difficult for us today to understand how contemporaries calculated that this space of just over 1,400 square metres could accommodate up to 3,000 visitors plus an orchestra and choir. The Bayernzelt at Pützchens Markt needs more than 2,000 square metres for such large numbers. In any case, the concerts are said to have been attended by around 2,000 people each. Incidentally, the hall was sold for demolition a few weeks after the end of the festival. The wish of the correspondent of the Leipziger Zeitung thus remained unfulfilled. At the end of September, he had wished the hall a long life as a music venue and not as a carnival’s hall. This is somewhat reminiscent of the current discussions about the use of today’s Beethoven Hall.

When Liszt arrived in Bonn a few weeks before the festival, at which he was to conduct alongside court conductor of Kurhessen Spohr, he immediately made his mark. He flatly rejected Breidenstein’s idea of using the Hussars’ riding arena in front of the northern city wall as a concert hall – according to a contemporary source, a ‘stinking hut’. The result was perhaps the greatest miracle in Bonn’s architectural history, which is otherwise not particularly rich in miracles: in less than two weeks, a consortium of Bonn carpenters, with the support of Cologne cathedral master builder Zwirner, erected a wooden festival hall in the ‘Raess’schen Gärten’. Today, we know this area as the car park in the Viktoriakarrée. With a height of around 7 metres, the building measured approximately 62 × 23 metres. However, it is difficult for us today to understand how contemporaries calculated that this space of just over 1,400 square metres could accommodate up to 3,000 visitors plus an orchestra and choir. The Bayernzelt at Pützchens Markt needs more than 2,000 square metres for such large numbers. In any case, the concerts are said to have been attended by around 2,000 people each. Incidentally, the hall was sold for demolition a few weeks after the end of the festival. The wish of the correspondent of the Leipziger Zeitung thus remained unfulfilled. At the end of September, he had wished the hall a long life as a music venue and not as a carnival’s hall. This is somewhat reminiscent of the current discussions about the use of today’s Beethoven Hall.

It was thanks in no small part to Liszt that hundreds of guests from out of town had gathered in Bonn on the eve of the celebrations. In addition to Beethoven enthusiasts including many Englishmen and a large group of Frenchmen led by Hector Berlioz, Liszt’s personal fan club also attended (mainly ladies who were almost hysterically devoted to him). Among them was the ‘it girl’ of her generation, Lola Montez, who was a dancer and always good for a scandal. How close she was to the maestro during those days was obvious.

The festival got off to a good start. The opening concert on the evening of August 10th, conducted by Louis Spohr, featured the Ninth and the Missa Solemnis. Even the critical critics were satisfied – although Spohr admitted that he had not known the Missa at all and had had to learn it in a crash course shortly before the concert. The next day was a day of rest, so to speak. The programme was limited to christening a ‘steamboat’ named Ludwig van Beethoven and taking it on a day trip to Nonnenwerth. On this and many other occasions, the people of Bonn held out their hands. The out-of-town guests found this unusual, and even local Gottfried Kinkel complained about the rampant commercialism and excessive merchandising.

The main reason for the festival, the unveiling of the monument on 12 August, was no longer under a lucky star. After a high mass in the cathedral, during which Berlioz had to climb over a barrier to reach his seat, the crowd gathered tightly packed on the cathedral square. It took an hour and a half before Their Highnesses, coming from Brühl, appeared on the balcony of the Fürstenberg Palace, today’s post office. The festive song composed by Breidenstein and ‘shouted by a male choir’ was blown away by the wind, as was his speech, which was delivered too quietly. The unveiling itself, however, was not the ‘scandal’ that many later generations would have us believe. Queen Victoria merely noted in her diary that it was unfortunate that the statue could only be seen from the back. It was not she, but King Frederick William IV who expressed his surprise, audible only to his immediate neighbours. Alexander von Humboldt, standing next to him, made the matter the most famous anecdote in Bonn’s city history with his reply: ‘Your Majesty, please bear in mind that Beethoven was also a rough fellow during his lifetime.’

The final day was the 13th and indeed an unlucky day. The grand morning ‘artists’ concert’ began an hour late, even though the king had asked for it to start without him and his guests. The egomaniac Liszt nevertheless delayed the start because he did not want to conduct his own cantata without royal accompaniment. This was untenable, but as luck would have it, the distinguished guests arrived just as the piece ended. So the maestro started from the beginning. The rest of the audience was not amused. After a few more items on the programme, the princes had to leave for Cologne to visit the cathedral. The audience was once again by themselves and had two more hours of music to endure. When it was time for lunch, most of the audience left the hall (‘Too much torment!’). The concert lasted until half past one.

The low point in the evening was reached at the banquet in the ‘Hotel zum goldenen Stern’ on the market square. Despite many toasts, Liszt did not acknowledge the French delegation. This led to turmoil and the ladies present fled. Only Lola Montez remained and danced on the table. Liszt had to lock her in her hotel room, where she promptly smashed the furniture.

Today’s Beethoven festivals are more civilised. The only reminder of 1845 is the iconic monument on Münsterplatz. And perhaps that’s just as well.

by Gert Fischer | May, 2025 | EN, famous people from Bonn, history

Apart from the seemingly inevitable local crime novels and a few autobiographical special cases, Bonn hardly ever appears as the setting for a novel. This also applies to its years as the capital city of Germany. Of the few novels that deal with the politics of the ‘Bonn Republic,’ Wolfgang Koeppen’s ‘Das Treibhaus’ (The Greenhouse) alone satisfies the highest literary standards as a roman à clef of the young Federal Republic. Unfortunately, it is hardly known outside Germany.

This means that Bonn makes only one appearance in world literature. It was created by John Le Carré (actually David John Moore Cornwell, 1931-2020) in his novel ‘A Small Town in Germany’, published in 1968. The author of The Spy Who Came in from the Cold and literary father of George Smiley is usually classified as a writer of pulp fiction in Germany. In the English-speaking world, he is rightly regarded as one of the most important authors of the recent past.

A Small Town in Germany is one of Le Carré’s lesser-known books. This may be because, unlike most of his works from the 1960s and 1970s, it does not revolve around the theme of the Cold War and does not feature the anti-Bond character George Smiley. Instead, the plot is embedded in the domestic politics of the Federal Republic of Germany and is therefore less accessible to an international audience than the global East-West conflict. It is set exclusively in Bonn and its immediate surroundings. Le Carré draws on his own experiences. From 1961 to 1963, he was stationed in Germany by the British Secret Service working undercover as Second Secretary at the British Embassy in Bonn. At that time writing was a part-time endeavour.

A Small Town in Germany is one of Le Carré’s lesser-known books. This may be because, unlike most of his works from the 1960s and 1970s, it does not revolve around the theme of the Cold War and does not feature the anti-Bond character George Smiley. Instead, the plot is embedded in the domestic politics of the Federal Republic of Germany and is therefore less accessible to an international audience than the global East-West conflict. It is set exclusively in Bonn and its immediate surroundings. Le Carré draws on his own experiences. From 1961 to 1963, he was stationed in Germany by the British Secret Service working undercover as Second Secretary at the British Embassy in Bonn. At that time writing was a part-time endeavour.

As Le Carré once remarked elsewhere, the plot takes place in the ‘near future’ from the year the book was published – if you look closely: in May 1970. The political panorama that forms the backdrop is bleak. Le Carré composes it from elements that helped shape the domestic politics of the Federal Republic in the 1960s, adding fictional and exaggerated elements to create an ugly dystopia: the grand coalition is still in power. The opposition FDP is infiltrated by shady figures with roots in the Nazi era. There is a powerful political alliance between the student movement and what we would today call right-wing populists. The target of their hatred is Great Britain. The Bundestag is still debating emergency laws, an amnesty for Nazi criminals comes into force, and accession negotiations between the EEC and Great Britain are going badly in Brussels. The country is on the brink of major unrest.

In this situation, a troubleshooter arrives in Bonn from London. A junior embassy employee has disappeared, apparently gone into hiding. Suspicions of espionage are rife. Alan Turner is tasked with getting to the bottom of the matter. Over the course of several weeks in May, he scrutinises the embassy’s operations, uncovers some of the staff’s dirty secrets and gets closer and closer to the man he is looking for, his character and his motives. This man is, if you will, the real protagonist of the novel. Yet he hardly ever appears in the book – only briefly at the beginning and end. This much can be revealed: it does not end well.

Le Carré’s picture of Bonn is as bleak as the plot. It begins with the weather – although it is May, it is consistently hazy and damp. There is no sign of warmth, and much of the action takes place at night. Le Carré anticipates an atmosphere that J.K. Rowling’s dementors would later spread. The city is cramped and narrow-minded – just like the republic that gave birth to it. This image is further embellished with all the prejudices that have always hurt Bonn’s local patriots: it rains, or the railroad crossing barriers are down; the nightlife is in Cologne; Bonn became the capital because Adenauer wanted it to be; it’s a waiting room for Berlin, etc. The tongue-in-cheek humour with which these sayings were often accompanied in Bonn is completely absent. The author is deadly serious. He even invents his own nastiness. In Bonn, even the flies are civil servants.

Woven into the backdrop of the book are many detailed descriptions. They range from the university and the railway station to the town hall and the British Embassy (sacrificed to Telekom in 2004) to the diplomatic settlements in Plittersdorf and Bad Godesberg. The protagonist lives on the slopes of the Petersberg, and the traffic problems are closely observed. Anyone reading the novel from this perspective may notice how Le Carré alters the city’s geography and even individual buildings to suit the needs of the plot. And, of course, he describes the buildings and structures as he remembers them from the early 1960s. They no longer correspond to the Bonn of 1970, let alone to the Bonn of today. Such a search for clues is great fun!

Why Bonn comes across so negatively in its only appearance in world literature remains an open question. It may have something to do with Le Carré’s bad memories of his time in Bonn. And, of course, it is also due to the dark subject matter. It may be comforting to know that he actually shows all the locations in his books from their ugly side. And perhaps there is a tiny grain of truth in his Bonn.

by Gert Fischer | May, 2025 | architecture, EN, Rhine region

Anyone strolling along Bonn’s Rhine promenade usually has their eyes fixed on the river and the sights on the horizon: the Siebengebirge mountains, the government district or the Schwarzrheindorfer Doppelkirche church, for example. But it’s worth taking a look to the right at the landing stage of the ‘Köln-Düsseldorfer’ shipping line. At the lower end of Vogtsgasse, in the shadow of the retaining wall of the Department of History, there is a small wayside shrine. It commemorates the Gertrudis Chapel, which stood a few metres away and has now been almost forgotten. Like the entire old town of Bonn, it was destroyed in the air raid of 18 October 1944. What remained of it was literally buried in the rubble. Shortly after the war, the mountains of debris in the city centre were used to raise the area between Belderberg and the banks of the Rhine by several metres. Unattractive new buildings from the 1950s were erected on what was once the ‘Rheinviertel’ (Rhine district).

The chapel was dedicated to Saint Gertrude of Nivelles, who lived in the first half of the 7th century. As a patron saint, she had a very broad portfolio. She was invoked against plagues of rats and mice (hence the mice as her attribute), and was considered the protector of travellers, pilgrims and sailors, gardeners, spinners and even cats. In addition, her historically documented commitment to nursing and the education of girls and women is still remembered today.

The chapel was dedicated to Saint Gertrude of Nivelles, who lived in the first half of the 7th century. As a patron saint, she had a very broad portfolio. She was invoked against plagues of rats and mice (hence the mice as her attribute), and was considered the protector of travellers, pilgrims and sailors, gardeners, spinners and even cats. In addition, her historically documented commitment to nursing and the education of girls and women is still remembered today.

It was probably these diverse connections that brought together a rather unlikely cooperation: the ‘Schiffer-Verein Beuel 1862’ (Beuel Boatmen’s Association), the Bonn Women’s Museum and the Bonn drag artist Curt Delander joined forces to ensure that the wayside shrine was built in memory of the chapel. It was built from bricks from the destroyed old town and stones from the St. Gertrudis Church in Nivelles (Belgium), which was destroyed by German bombs. This makes it a small memorial to peace, and it also reminds us that reconciled enemies drank the ‘St. Gertrudis Minne’ in the Middle Ages.

The building, which was destroyed in 1944, was not an architectural gem and no longer had any great spiritual significance. It was a simple single-nave hall building from the 15th century with modest furnishings. It was originally located directly behind the city wall next to the ‘Gierpforte’ whose name is derived from ‘Gertrud’. Even after the wall was demolished in the 19th century, there was no unobstructed view of the Rhine. A hotel building between the riverbank and the chapel ensured that the backyard situation remained unchanged. The parish church of the district was St. Remigius on what is now Remigiusplatz, with the Gertrudiskapelle chapel merely a branch. For a long time, its main users were the local boatmen and their brotherhood. This Cinderella existence may explain why there was hardly any opposition to the demolition of the little church.

The building, which was destroyed in 1944, was not an architectural gem and no longer had any great spiritual significance. It was a simple single-nave hall building from the 15th century with modest furnishings. It was originally located directly behind the city wall next to the ‘Gierpforte’ whose name is derived from ‘Gertrud’. Even after the wall was demolished in the 19th century, there was no unobstructed view of the Rhine. A hotel building between the riverbank and the chapel ensured that the backyard situation remained unchanged. The parish church of the district was St. Remigius on what is now Remigiusplatz, with the Gertrudiskapelle chapel merely a branch. For a long time, its main users were the local boatmen and their brotherhood. This Cinderella existence may explain why there was hardly any opposition to the demolition of the little church.

Despite its unattractive exterior and its minor importance at the time, the Gertrudiskapelle was considered the ‘most distinguished’ church in Bonn after the cathedral in the oral tradition of the 19th century. Even back then, this statement did not fit with what was known about its history: first mentioned in 1258, a small hermitage of Cistercian nuns, later a temporary home for Capuchin and Franciscan Recollect monks – each before they moved into their spacious new monasteries. In 2010/11, an archaeological excavation with sensational results revealed just how much truth there can be in oral tradition. It found the remains of two previous buildings – the earliest dating from the 8th century and thus Carolingian and about as old as the two oldest inner-city parish churches, St. Remigius and St. Martin. It is very likely that this first chapel was dedicated to St. Gertrude. This can be deduced from the fact that, like Remigius and Martin, the name was often used for churches in the Carolingian period – no wonder, since the historical Gertrude was one of the leading figures in the lineage of Charlemagne.

We do not know whether this first Gertrudis Chapel was built as a parish church or whether it has a different origin. In any case, by the middle of the twelfth century, it must have been the spiritual centre of a fairly extensive settlement along the Rhine, as evidenced by archaeological finds. This settlement lost much of its importance during the Middle Ages, and with it the Church of St. Gertrude. Today, the small wayside shrine on Vogtsgasse is the last link to this period.

by Gert Fischer | Mar, 2025 | EN, points of interest, tradition

With the Old Cemetery in the city centre, the Bad Godesberg Castle Cemetery and the Poppelsdorf Cemetery, Bonn has three outstanding burial sites due to their significance, ambience or location. If you add to this the village churchyards in some districts that are still preserved and date back even further, Bonn’s cemetery landscape is almost worth a trip. This historical heritage overshadows the more modern facilities.

Photo: A. Savin

Thus, Bonn’s largest cemetery by far, the Nordfriedhof on Kölnstraße in today’s Auerberg district, is perhaps the Cinderella of cemeteries. Opened in 1884 as the official successor to the Old Cemetery, which could no longer be expanded, the Nordfriedhof got off to a bad start mainly due to its location. More than three kilometres from the centre of Bonn, it was on the far northern outskirts of the city. It only received a rail connection in 1906, when the Rheinuferbahn (Rhine bank railway) started operating. In the first decades of its existence, it was located in an open field. On the way there, you passed the smouldering rubbish heap where today’s Sportpark Nord is located, the Rheinische Provinzial-Irrenanstalt (today the LVR-Klinik Bonn), the Städtische Hilfshospital für Geisteskranke, Epileptiker und Trunksüchtige (a municipal hospital for the mentally ill, epileptics and alcoholics) and the orphanage and correctional home, which was located on the former site of the leprosarium (an isolation ward for infectious diseases). And contemporaries were certainly also aware that the cemetery area included the former place of execution with the gallows and the Schindanger, where animal carcasses that could no longer be used were disposed of. It is therefore not surprising that the so-called ‘better circles’ at the time sought burial sites elsewhere. After 1905, this was also officially possible. Those who lived ‘west of the railway’ could be buried in the cemetery of the recently incorporated Poppelsdorf. The inhabitants of the southern and western parts of the city made ample use of this opportunity. The Nordfriedhof thus became the cemetery for the city centre and the northern part of the city. Accordingly, the names of the families buried here that are significant in local history are linked to this part of the city. The graves of professors and wealthy individuals were buried mainly in the Poppelsdorf Cemetery, as were those of many of Bonn’s dignitaries.

Nevertheless, the North Cemetery gradually gained its place in the Bonn cemetery landscape. It changed for the better as a park, designed in an exemplary manner including a large chapel added in 1913. Its subsequent three expansions prove that it has become a popular cemetery. Even the reckless handling of some of its remnants could not prevent this. In the 1960s, for example, rows of gravestones were cleared when the main entrance was widened, and the neo-Romanesque gate was demolished. As a result, the list of ‘preserving-worthy’ grave monuments is short compared to the size of the cemetery.

The character of the Nordfriedhof as a cemetery of honour represents a special chapter. The beginnings of this development lie in the First World War. Today, not only the German victims of two world wars are buried here, but also numerous forced and foreign labourers as well as prisoners of war. Initially a place of local remembrance, the war cemetery and cemetery of honour became the central ‘Memorial of the Federal Republic of Germany for the Victims of War and the Victims of Tyranny’ in 1980 (today in Berlin at the Neue Wache). At that time, the bronze plate designed by Hans Schwippert – known as the architect who converted the Pedagogical Academy into the Bundeshaus and Palais Schaumburg into the Federal Chancellery – was transferred from the Hofgarten to the Nordfriedhof for this purpose. One of the more embarrassing chapters in Bonn’s history is that in 2017 it was stolen and replaced by a copy in sandstone.

As a relatively modern cemetery, the Nordfriedhof was not consecrated by a Catholic priest and was not bound to historical structures. Therefore, it reflects the developments that have shaped the funeral industry in the recent past better than many older cemeteries and those that are subject to preservation orders that restrict them to an earlier state. For example, a Yazidi cemetery is integrated into the Nordfriedhof. There are graves where the Greek Orthodox or Russian Orthodox rites were observed, as well as an area for children who died in the womb or at birth. And since 1990, it has had an Islamic burial ground.

A walk through the Nordfriedhof Cemetery is therefore not so interesting if you are interested in art, historically significant graves and famous names. Rather, it is a generously laid out park that reflects the social structure of Bonn city centre and the north of Bonn. Nevertheless, exciting discoveries are not out of the question. For example, there are three graves of members of the Sikh religious community who came to Bonn with the British occupation troops after the First World War. Or the grave of the singer and entertainer Fereydun Farrochsad, who was murdered in Bonn in 1992 in the name of the Islamic revolution in Iran.

Furthermore, the Nordfriedhof is of ecological interest. It has remarkable trees and, due to its size, a wide variety of animal and plant life. With the support of the Rotary Club, the city of Bonn is using it as an experimental area for ‘future trees’ – as a ‘climate grove’.

It is to be hoped that the restoration work on the cemetery chapel, which has been going on for two years now, will finally be completed. Until then, funeral services are held in an unworthy plastic tent. The North Cemetery is still worth a visit!

The so-called ‘Old Cemetery’ is easy to overlook. It is surrounded by walls and squeezed between three main roads and the railway line. Its entrance is at the beginning of Bornheimer Straße, almost directly next to the town hall. When you walk through the gate you enter another world. Graves from times long past lie in the shade of tall trees. Weathered gravestones and rusted wrought-iron crosses dominate the scene. Some are crooked. Many of the graves are obviously no longer maintained and are overgrown. The traffic noise fades into the background and birdsong dominates. It is no wonder that feature films are occasionally shot here. Fog machines are turned on and eerie figures stride through the night. The rattling of the railway is suppressed.

The so-called ‘Old Cemetery’ is easy to overlook. It is surrounded by walls and squeezed between three main roads and the railway line. Its entrance is at the beginning of Bornheimer Straße, almost directly next to the town hall. When you walk through the gate you enter another world. Graves from times long past lie in the shade of tall trees. Weathered gravestones and rusted wrought-iron crosses dominate the scene. Some are crooked. Many of the graves are obviously no longer maintained and are overgrown. The traffic noise fades into the background and birdsong dominates. It is no wonder that feature films are occasionally shot here. Fog machines are turned on and eerie figures stride through the night. The rattling of the railway is suppressed. Another treasure of the Old Cemetery is its trees, some of which date back to the 19th century. This is where problems become apparent: in some places, monument preservation and nature conservation compete with each other, as the tree roots threaten historic graves. Nowhere is this more evident than at the grave of Ernst Moritz Arndt, where the oak tree he planted himself almost 200 years ago is in the process of overturning the gravestones.

Another treasure of the Old Cemetery is its trees, some of which date back to the 19th century. This is where problems become apparent: in some places, monument preservation and nature conservation compete with each other, as the tree roots threaten historic graves. Nowhere is this more evident than at the grave of Ernst Moritz Arndt, where the oak tree he planted himself almost 200 years ago is in the process of overturning the gravestones.

The occasion for the celebrations was not only the 75th birthday of the master, who died in 1827, but above all the inauguration of the Beethoven monument by the Dresden sculptor

The occasion for the celebrations was not only the 75th birthday of the master, who died in 1827, but above all the inauguration of the Beethoven monument by the Dresden sculptor  When Liszt arrived in Bonn a few weeks before the festival, at which he was to conduct alongside court conductor of Kurhessen Spohr, he immediately made his mark. He flatly rejected Breidenstein’s idea of using the Hussars’ riding arena in front of the northern city wall as a concert hall – according to a contemporary source, a ‘stinking hut’. The result was perhaps the greatest miracle in Bonn’s architectural history, which is otherwise not particularly rich in miracles: in less than two weeks, a consortium of Bonn carpenters, with the support of Cologne cathedral master builder Zwirner, erected a wooden festival hall in the ‘Raess’schen Gärten’. Today, we know this area as the car park in the Viktoriakarrée. With a height of around 7 metres, the building measured approximately 62 × 23 metres. However, it is difficult for us today to understand how contemporaries calculated that this space of just over 1,400 square metres could accommodate up to 3,000 visitors plus an orchestra and choir. The Bayernzelt at Pützchens Markt needs more than 2,000 square metres for such large numbers. In any case, the concerts are said to have been attended by around 2,000 people each. Incidentally, the hall was sold for demolition a few weeks after the end of the festival. The wish of the correspondent of the Leipziger Zeitung thus remained unfulfilled. At the end of September, he had wished the hall a long life as a music venue and not as a carnival’s hall. This is somewhat reminiscent of the current discussions about the use of today’s

When Liszt arrived in Bonn a few weeks before the festival, at which he was to conduct alongside court conductor of Kurhessen Spohr, he immediately made his mark. He flatly rejected Breidenstein’s idea of using the Hussars’ riding arena in front of the northern city wall as a concert hall – according to a contemporary source, a ‘stinking hut’. The result was perhaps the greatest miracle in Bonn’s architectural history, which is otherwise not particularly rich in miracles: in less than two weeks, a consortium of Bonn carpenters, with the support of Cologne cathedral master builder Zwirner, erected a wooden festival hall in the ‘Raess’schen Gärten’. Today, we know this area as the car park in the Viktoriakarrée. With a height of around 7 metres, the building measured approximately 62 × 23 metres. However, it is difficult for us today to understand how contemporaries calculated that this space of just over 1,400 square metres could accommodate up to 3,000 visitors plus an orchestra and choir. The Bayernzelt at Pützchens Markt needs more than 2,000 square metres for such large numbers. In any case, the concerts are said to have been attended by around 2,000 people each. Incidentally, the hall was sold for demolition a few weeks after the end of the festival. The wish of the correspondent of the Leipziger Zeitung thus remained unfulfilled. At the end of September, he had wished the hall a long life as a music venue and not as a carnival’s hall. This is somewhat reminiscent of the current discussions about the use of today’s

A Small Town in Germany is one of Le Carré’s lesser-known books. This may be because, unlike most of his works from the 1960s and 1970s, it does not revolve around the theme of the Cold War and does not feature the anti-Bond character George Smiley. Instead, the plot is embedded in the domestic politics of the Federal Republic of Germany and is therefore less accessible to an international audience than the global East-West conflict. It is set exclusively in Bonn and its immediate surroundings. Le Carré draws on his own experiences. From 1961 to 1963, he was stationed in Germany by the British Secret Service working undercover as Second Secretary at the British Embassy in Bonn. At that time writing was a part-time endeavour.

A Small Town in Germany is one of Le Carré’s lesser-known books. This may be because, unlike most of his works from the 1960s and 1970s, it does not revolve around the theme of the Cold War and does not feature the anti-Bond character George Smiley. Instead, the plot is embedded in the domestic politics of the Federal Republic of Germany and is therefore less accessible to an international audience than the global East-West conflict. It is set exclusively in Bonn and its immediate surroundings. Le Carré draws on his own experiences. From 1961 to 1963, he was stationed in Germany by the British Secret Service working undercover as Second Secretary at the British Embassy in Bonn. At that time writing was a part-time endeavour.

The chapel was dedicated to Saint Gertrude of Nivelles, who lived in the first half of the 7th century. As a patron saint, she had a very broad portfolio. She was invoked against plagues of rats and mice (hence the mice as her attribute), and was considered the protector of travellers, pilgrims and sailors, gardeners, spinners and even cats. In addition, her historically documented commitment to nursing and the education of girls and women is still remembered today.

The chapel was dedicated to Saint Gertrude of Nivelles, who lived in the first half of the 7th century. As a patron saint, she had a very broad portfolio. She was invoked against plagues of rats and mice (hence the mice as her attribute), and was considered the protector of travellers, pilgrims and sailors, gardeners, spinners and even cats. In addition, her historically documented commitment to nursing and the education of girls and women is still remembered today. The building, which was destroyed in 1944, was not an architectural gem and no longer had any great spiritual significance. It was a simple single-nave hall building from the 15th century with modest furnishings. It was originally located directly behind the city wall next to the ‘Gierpforte’ whose name is derived from ‘Gertrud’. Even after the wall was demolished in the 19th century, there was no unobstructed view of the Rhine. A hotel building between the riverbank and the chapel ensured that the backyard situation remained unchanged. The parish church of the district was St. Remigius on what is now Remigiusplatz, with the Gertrudiskapelle chapel merely a branch. For a long time, its main users were the local boatmen and their brotherhood. This Cinderella existence may explain why there was hardly any opposition to the demolition of the little church.

The building, which was destroyed in 1944, was not an architectural gem and no longer had any great spiritual significance. It was a simple single-nave hall building from the 15th century with modest furnishings. It was originally located directly behind the city wall next to the ‘Gierpforte’ whose name is derived from ‘Gertrud’. Even after the wall was demolished in the 19th century, there was no unobstructed view of the Rhine. A hotel building between the riverbank and the chapel ensured that the backyard situation remained unchanged. The parish church of the district was St. Remigius on what is now Remigiusplatz, with the Gertrudiskapelle chapel merely a branch. For a long time, its main users were the local boatmen and their brotherhood. This Cinderella existence may explain why there was hardly any opposition to the demolition of the little church.

Recent Comments